An academic population model to distill the ‘PhD Problem’

UPDATE: Wanted to add this link for an ESA lunch session on Aug. 6 called “Beyond Academia“.

In the past year or two there has been a deluge of articles (e.g., this, this, and this) and blog posts (e.g., this and this) written about the so-called “PhD Problem.” The essence of the problem is that we (academia) don’t have enough tenure-track jobs to possibly absorb all the PhD students. What this means is that many newly-minted PhD’s that want to go into academia (and even those that don’t want to go into academia, since our training is generally academic-oriented) have poor job prospects. Competition for a faculty position is very high, and good luck trying to choose where you end up (unless you’re a rock star). Academia is a pyramid scheme.

But, Jacquelyn Gill over at the Contemplative Mammoth wrote a great piece on how we don’t really have a PhD problem, but instead an attitude problem. The problem is that we are 1) not training graduate students well for positions outside of academia and 2) we aren’t doing a good job at selling our desirable skills outside of academia. Further, she suggests doing these things are critical because there are many PhD students that don’t even want to be a professor. In sum, Jacquelyn proposes that we do not need fewer PhD students, we just need them to leave academia afterward (which, I want to be clear, is not a judgmental statement; leaving academia for a different career path is not a “failure”, and it doesn’t mean leaving science).

I am all for this. It would help those who want a PhD and want to pursue work outside of academia, and it might lessen the degree of our current PhD problem. But still, it seems to me we would need current graduate students to want to leave academia in a huge proportion. Some of my results below indicate the large gap in proportions that would need to be lessened. This means we need to focus on various fronts to tackle the PhD problem, both in terms of training and in terms of the rates at which people enter and leave academia. Sounds like a great problem for a model.

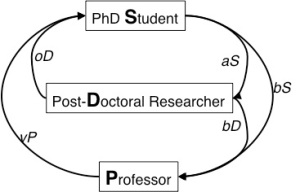

I’m going to build a very simple population dynamic model of academia. Let’s assume for simplicity that the limiting factor in all of this is money (after all, if there was just more money, universities could hire more faculty — not necessarily the case, but bear with me on this). The model is monetarily-implicit, just like how some population models of, say, plants are spatially-implicit — each person needs a “money patch” to survive, but we’re not actually going to model the transfer of money in any real way. All patches of money are always occupied by PhD students (S), postdoctoral researchers/fellows (D), or professors (P). The default state is the PhD student (S), so whenever a post-doc leaves his/her position (through attrition, not by moving up to faculty) or a professor retires, that money patch reverts to a PhD student. Basically, we can think of PhD students as some plant with a good seed source and good dispersal — if there is an open patch, a PhD student will be able to fill it!

To establish a monetary hierarchy, postdocs can only establish on PhD patches, whereas professors can establish on postdoc or PhD money patches. Basically, this assumes that money preferentially goes to professors, then post docs, the grad students. But, since it costs more to fund a postdoc or professor relative to a PhD student, a postdoc requires 2 student money patches and a professor requires 4 student money patches (and then a professor requires 2 postdoc money patches). Postdocs establish at rate a, which is dependent upon the relative abundance of PhD students, since they can only establish on those patches. Professors establish at rate b, which is dependent upon the relative abundance of PhD students + postdocs. Postdoc attrition rate is o, and professor retirement rate is v.

Let S = PhD students, D = postdoctoral researchers/fellows, and P = professor (Assistant through Full). The simple population dynamic model of academia is then three differential equations that represent the instantaneous rate of change for each of the three states:

$latex frac{dS}{dt} = vP + oD – afrac{S}{2} – bfrac{S}{4}&bg=ffffff$

$latex frac{dD}{dt} = afrac{S}{2} – bfrac{D}{2} – oD&bg=ffffff$

$latex frac{dP}{dt} = b(frac{S}{4}+frac{D}{2}) – vP&bg=ffffff$

and the parameters, with ecological analogues in parentheses, are:

v = professor retirement rate (mortality of professors)

o = postdoctoral researcher attrition rate (mortality of postdocs)

a = postdoc establishment rate (birth rate of postdocs)

b = professor establishment (the birth rate of professors).

These are all annual rates, so v = 0.05 means a 5% per year retirement rate. The model is run on yearly time-steps.

Here’s a schematic of what the model looks like.

Remember, the flows aren’t necessarily stage-structured. For example, aS does not really show the recruitment of a PhD student to the post-doc stage, but more explicitly a post-doc establishing on a PhD “money patch.” This can be interpreted as a PhD leaving the PhD cohort and moving to the post-doc stage, but we aren’t following individuals here — the flow of a PhD to post-doc (aS) DOES NOT leave an empty patch for a new PhD. New PhDs only establish when a professor retires or a post-doc leaves the system — this is of course not how it really works, but I think the model can still pick up the general population dynamics.

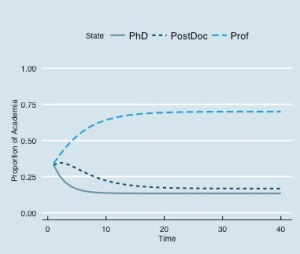

Since this model is so simple*, it reaches equilibrium really fast on yearly timesteps. So, I’ll just show some numerical results of running the model through time. Let’s think about an ideal world in terms of the rates a, b, o, and v. Ideally, at least in my thinking, we all would want relatively high establishment rates, and low attrition and retirement rates. From that statement alone I bet you can guess the problem! Here is the equilibrium result when a = 0.5, b = 0.3, and o = v = 0.05 (i.e., 5% retirement and attrition rate; Figure 1).

Uh-oh! If this is the ideal, and probably pretty close to actual rates, then that means our actual situation (high proportion of PhD students) is not at equilibrium and wildly unstable (which we knew, right)! What kind of values would it take to get a proportion more like what we actual have in academia?

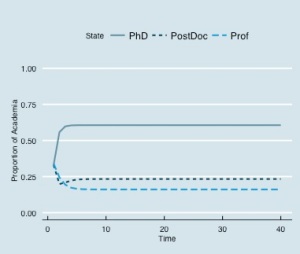

You guessed it, higher attrition and retirement rates. Here is the result (Figure 2) with higher attrition and mortality rates (a and b are the same as above). Keeping a and b constant, I had to bump the retirement and attrition rates of professors and postdocs, respectively (and respectfully of course) over 50% in order to get the propotion of PhD students to be greater than the proportion of professors (our current situation). That means 50% of professors would have to retire every year! Not likely, and as someone that wants to be a professor, that doesn’t sound good.

So, what can we do? Well, the great thing about using simple models like this is that it is easy to see where we need to make changes. Obviously, we need to increase the rates o and v. We can also just reduce the number of PhD students to reduce their contribution to the population percentages. Which of these are actionable? In my mind, reducing the number of PhDs (either through stricter standards or having them leave academia for other fulfilling employment) and increasing the retirement rate of professors are the two really actionable items. By the time someone is a postdoc they are pretty committed to academia, so it is doubtful we can raise the attrition rate there.

Are these things we really want to do? I’d argue that there is no downside to making it harder to get a PhD. Eventually there is a bottle neck where competition for employment within the academy is insanely high. Right now it is at the postdoc-to-faculty stage. Why not make it sooner so people can get on with their lives before becoming overly committed to academia?

Now, what about a mandatory retirement age for faculty? This will be met with uproar! As someone who wants to be a professor and work well into my old age, I don’t even like this one (I like it right now, of course, because it would benefit me getting a job. But after that I would want to repeal the retirement clause!). But maybe these are conversations we need to be having. Another option, even more incendiary, that some people I’ve chatted with have mentioned is getting rid of tenure and treating the academic world more like the results-based private sector.

What do you think? How do we go about solving this problem?

Do you think this model gets at the important rates? Or, should it be more mechanistic, with PhDs and postdocs being tied to individual professors through the money they bring in?

*Yes, I completely recognize just how simple and unrealistic the model is, but let’s run with it for now. In the comments, let me know what you think should be added (Lotka-Volterra type dynamics with density-dependence? Stage-structure?). You can access the basic model used in this post here.