The Critical Nature of Women’s Knowledge for Local Conservation: Reflections from a PhD Student’s Ongoing Work in Ethiopia

A November 2013 EcoPress posting by Kate Wilkins astutely points out the under-representation of women in leadership positions linked with sustainable development in the U.S. and the implications of this lack of empowerment for conservation and sustainability. For some time I failed to think of such disheartening and historically constant facts beyond the realm of academia and industry in advanced developed nations, or explicitly acknowledge their intimately linked nature with the array of gender inequality issues plaguing the developing world, including the African continent. This recent realization struck a chord with me both personally and as a research scientist, and my growing understanding of the universally diffuse nature of gender inequality in science, conservation, and sustainability has placed the importance of women’s local ecological knowledge at the forefront of my research.

Going into my PhD, I never would have imagined my work would explicitly focus on gender, let alone be based predominately in the remote southern highlands of Ethiopia. Jumping at the opportunity to travel to Ethiopia in December 2012 with my co-advisor Paul Evangelista and a small team of CSU colleagues from the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory, I was able to craft part of a study exploring the plant knowledge of local agro-pastoralists in a country that has captivated my imagination for a number of years. With a generous fellowship through Colorado State University’s Center for Collaborative Conservation, and the support of the 501(c)(3) non-profit The Murulle Foundation, I was able to engage my curiosity about local plant knowledge in the Bale Mountains and assess the importance of gender-based differences in local ethnobotanical knowledge. Plants play a critical role in the daily lives of Ethiopians- some 80% of rural Ethiopians rely on plant-based medicine as their primary healthcare and around 90% of people in the southern highlands depend on small-scale, rain-fed agriculture (Bekalo et al., 2009; Zeleke, 2010). I had hoped to understand and help preserve this important cultural knowledge; specifically, the knowledge of women, whose distinct way of knowing the landscape is often overlooked.

The wonders of Ethiopia cannot be overstated. As the headwaters of the Blue Nile, Ethiopia provides the majority of water for both tributaries of the longest and most recognizable river in the world. The earliest known direct predecessor of humans, Ardipithecus ramidus, or “Ardi” for short (4.4 million years old), and her slightly younger but more famous pre-human sister, Australopithecus afarensis, named “Lucy” (3.2 million years old), were both discovered in the arid landscape of northern Ethiopia.

The lush, forested southern reaches of the country are just as captivating and home to some of the most spectacular biodiversity in the world, with rare and endemic fauna like the endangered mountain nyala (Tragelaphus buxtoni), a large spiral horned antelope, and the critically endangered Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis).

The Bale Mountains National Park, located adjacent to one of my project sites, is noted to be among the world’s most irreplaceable Protected Areas for conservation of amphibian, bird and mammal species (LaSaout teal., 2013). The flora is equally impressive with the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) noting that “…the conditions and the isolation of these areas have led to the evolution of unique plant communities that are found nowhere else” (UNEP, 2008). This has led to a proposal for designating the Bale Mountains National Park a United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site.

My time was spent in the southern portion of the country, in the high montane forests constituting part of the greater Bale-Arsi Massif, which reach up to 4,377 meters (14,360 feet) elevation. Hiking in the depths of the Afro-montane forest, I was amazed at how lush and green the vegetation was, and the fairly cool to downright cold temperatures that persisted underneath the canopy of thick tree tops and serpentine branches blanketed with epiphytes and sinewy mosses. The agro-pastoralists of this region are ethnic Oromo and primarily cultivate barley, but also herd a mixture of cattle and goats; the Oromo have a deep connection to the landscape linked with their subsistence practices.

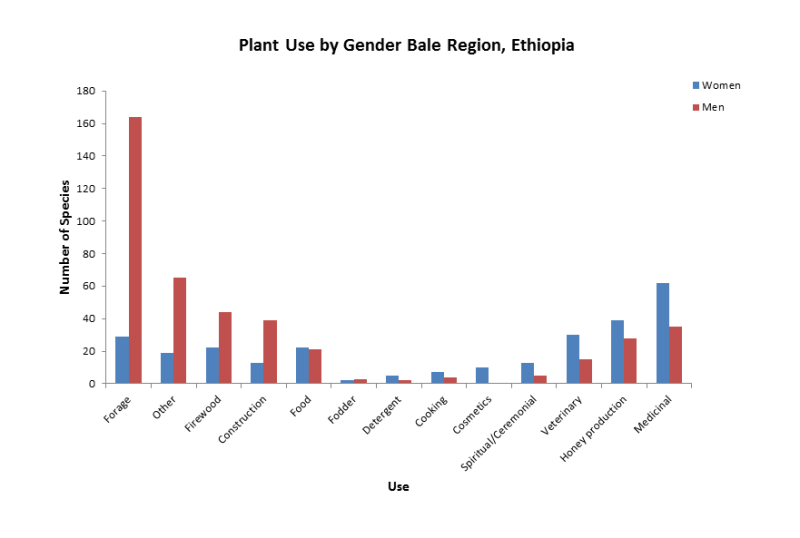

My team was provided the opportunity to interview two groups of local women that live adjacent to the National Park about local plant knowledge. Building on existing research of men’s ethnobotanical knowledge in the Bale Mountains (Bussmann et al., 2011), semi-structured focus groups were conducted to catalogue women’s floristic knowledge. These focus groups were led by Heather Young, an environmental educator with Larimer County Natural Resources; Christina Kuroiwa, a doctor from Colorado State University who has worked extensively with indigenous communities around the world; and our local Ethiopian friend, translator, driver and tracker-extraordinaire, Aserat Worede. The ethnobotanical data collected were examined in an effort to understand gender-based differences in knowledge and use of plant-derived provisioning ecosystem services (i.e. the material and energetic outputs of an ecosystem, including tangible things that can be directly consumed, exchanged or used by people). For nearly six hours at each location we identified plants from a pool of over 360 plant identification pictures spread out on table tops. The pictures were grouped according to their growth form (e.g. fern, grass, tree, shrub), and the women were encouraged to take as much time as they felt necessary to converse with each other and walk around the room while examining the photos. All of the women collected pictures of plants they recognized, and once everyone had finished, we sat down as a group and went through each plant individually to discuss their local names and their derived uses. The women at one of the interview sites shared detailed stories, discussed the environmental changes they had recently witnessed – including erratic precipitation patterns and the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters like drought and flooding – and shared detailed knowledge about and array of plants (Luizza et al., 2013). The women identified a number of distinct uses from those of men. For example, the shrub Carissa edulis (or “Agempsa” in the local Oromiffa language) was noted by men to provide forage services, acting as food for livestock and wildlife. The women, however, explained that the plant’s fruits were edible and that it also acts as a human food source; additionally, Agempsa provides cosmetic services as the thorns are used for piercing ears.

Beyond individual plants, important differences in knowledge regarding plant-use categories were revealed when comparing the men and women’s data across the multiple interview sites within the region. Overall, women identified nearly twice as many medicinal and veterinary plants as men, while men identified six times as many forage plants and three times as many plants used for construction.

These preliminary findings reveal a need to include a gendered understanding of plants when cataloguing this important cultural knowledge. Moreover, the women from one of our interview sites also brought up future project ideas that include creating a local seed bank and pooling money to purchase land outside of the town to grow medicinal plants to sell at the market. They were even interested in us coming back and facilitating a youth education program led by the women, where they would teach local girls about the plants in the area. We are currently working on acquiring funding for this workshop as we prepare for our upcoming trip in April of this year. This amazing experience in Ethiopia has played an important role in my PhD dissertation research, and has set the stage for what I hope is a long-term collaboration with local communities in the Bale Mountains. Such work has posed major challenges but has also provided great insight to the powerful and unique contributions of women to conservation and sustainability. Furthermore, the growing network of scholars, practitioners and students addressing this issue head-on, as seen for example with the Global Women Scholars Network, further instills hope that such work holds great value for empowering individuals, fostering scientific advancement and promoting resilient landscapes while protecting human well-being; tangible effects that can and will increasingly be felt around the world.

References:

Bekalo, T.H., Woodmatas, S.D., and Woldemariam, Z.A. 2009. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants used by local people in the lowlands of Konta Special Woreda, southern nations, nationalities and peoples regional state, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 5: 26-40.

Bussmann, R.W., Swartzinsky, P., Worede, A., and Evangelista, P. 2011. Plant use in Odo-Bulu and Demaro, Bale region, Ethiopia. Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine, 7: 28-48.

LeSaout, S., Hoffman, M., Shi, Y., Hughes, A., Bernard, C., Brooks, T.M., Bertzky, B., Butchart, S.H.M., Stuart, S.N., Badman, T., and Rodrigues, A.S.L. 2013. Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science, 342(15): 803-805.

Luizza, M.W., Young, H., Kuroiwa, C., Evangelista, P., Worede, A., Bussmann, R.W., and Weimer, A. 2013. Local knowledge of plants and their uses among women in the Bale Mountains, Ethiopia. Ethnobotany Research and Applications, 11:315-339.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2008. Africa: Atlas of Our Changing Environment. Division of Early Warning and Assessment (DEWA). Nairobi: Kenya.

Zeleke, G. 2010. A Study on Mountain Externalities in Ethiopia (Final Report). Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations: Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Development Mountain Policy Project. Addis Ababa: Ethiopia. Retrieved from: http://www.fao.org/sard/common/ecg/3252/en/Mountain_Externalities_in_Ethiopia.pdf.

Matt Luizza is an ecology PhD candidate in the Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory and Department of Political Science at Colorado State University, with co-advisors Michele Betsill and Paul Evangelista. All photos by Matt Luizza.